With the UK general election 2015 only a few weeks away (May 7th), the major parties’ campaigns have become hot topics across British political online platforms, which in turn caused the formation of a nationally oriented web sphere that is not only moulded by the classic Tory-Labour fault line but has extended to the (former) political fringes, especially on the right with the growing importance of the Eurosceptic UKIP . To promote their framings for current issues in UK politics in the public sphere all major political players, media observers, and commentators disperse polarising problem definitions, causal interpretations, ethical judgements, and – most importantly for the election context – recommendations for actions (Entman 1993) based on seemingly irreconcilable values.

I think it is in this respect appropriate to take a look back at the last general election in 2010, for which each political party invested considerable efforts into online campaigning. Back then I conducted a comparative content analysis of British political web blogs with a focus on the general election for my MA thesis at Coventry University.

The main research question were: how open are political online platforms in terms of a pluralism of attitudes/opinions? How do sub-genres of political blogs differ in regards to their discourse potential? Who does actually partake in online debates via commenting and how do they express their opinions? The sample included online articles and their comment sections from twelve popular British political online platforms and news media sites published between April 6th and May 5th 2010:

- Conservative Home (party blog)

- Labour List (party blog)

- LibDem Voice (party blog)

- Guy Fawkes (A-list blogger)

- Iain Dale (A-list blogger)

- Charlotte Gore (A-list blogger)

- Liberal Vision (A-list blogger)

- Hopi Sen (A-list blogger)

- Next Left (A-list blog/party blog hybrid)

- the Guardian Online (News media)

- the Times Online (News media)

- Daily Mirror Online (News media)

The platforms were separated into three larger categories, which are political party blogs, “independent” but politically-affiliated A-List bloggers, and news media sites. Altogether the selected weblogs/websites produced 3150 articles with 105293 comments left by readers who engaged in relatively few but partly quite intensive follow-up discussions. Due to certain practical limitations (this was a only an MA thesis), the enormous amount of potential research subjects had to be reduced; otherwise the study would have remained unfeasible to accomplish with the given temporal and human resources at my disposal (less than three months, one graduate student).

The empirical sample eventually included 120 articles and 2286 comments; this is less than ten percent of the total population and all claims must be interpreted with clear limitations to the overall representability of the final analysis.

However, since it was a pilot study that analysed an equal amount of articles per platform in considerable detail, I think its results are still interesting for the assessment of current modes of political online communication in the UK election context. The most important findings concern the limited levels of dialogue, tendencies towards fragmentation, verbal/textual violence, and the digital transformation of public discourse. It became quickly apparent that online media indeed played a central role in the election campaigns across the British political landscape – with ambivalent implications for trends in political online communication and public debates.

“No Response” – Limited Levels of Dialogue

There was considerable activity on part of the different communicators, i.e. operators of the sampled websites, who produced large amounts of content on a daily basis (over 3500 in four weeks). These articles also stimulated on-site communication in form of commenting in even larger quantities (over 105000).

However, it seemed that this high-frequency level of online communication seldom transformed into genuine dialogues or deliberation-based discussions. For example, less than half of all comments in the sample were directly connected to each other; readers did express their opinions in various forms but only in a few instances longer exchanges of arguments took place.

A lot of people posted their comments but most never stimulated any responses from neither the post’s author(s) nor other readers. In fact, most bloggers and journalists hardly engaged in the comment sections at all and left the field entirely to their site visitors.

Only a few bloggers – e.g. Hopi Sen or Charlotte Gore – engaged on the comment level with their audiences in mentionable frequencies, if compared to the other websites in the sample. However, only a fraction of these responses dealt with actual political issues; most were mere expressions of gratitude, approval, or non-political messages in irrelevant, de-contextualised side debates.

To sum up, the different online platform hardly became integrative-democratic stages for the reasoned exchanged of arguments but rather resembled transmitters for unidirectional communication flows and collections of mostly isolated messages that did not condense into meaningful conversation.

Fragmenting Tendencies

Though the majority of commenting users did not express any distinct ideological affiliation, many platforms still showed tendencies towards political fragmentation or balkanisation (Sunstein 2007).

Quite unsurprisingly, it were party blogs in particular that seemed to attract like-mined people in the respective comment sections.

The findings implied that back in 2010 users with similar political attitudes tended to “flock” on the same online platforms. This does not mean that there were no comments that expressed diverging opinions at all, but it happened only occasionally that a staunch conservative left a message on a Labour blog and vice versa. This probably limited the chances for real on-site contestation between site visitors on party- and A-list blogs. However, in these particular contexts forms of in-group deliberation sometimes materialised:

On news media sites, due to their broader scope, the situation looked a bit different and a polarising attitudes beyond the context of intra-party micro-politics met in higher frequencies. Quite interestingly, over half of all posted comments on party- and A list blogs were not directly related to the actual article but dealt with some form of side issue or sub-topic; these were not always “political” in a strict sense but focused on “soft issues” (jokes, socialising between users etc.). The analysis showed that conservatives were especially “talkative” on their respective websites/blogs:

The UK’s political right appeared extremely active on the Web and aggressively campaigned against the then-ruling Labour government.

Exclusion and Verbal/Textual Transgression

The analysis further showed that only a small group of highly engaged users produced the majority of comments, who probably presented a mere fraction of the UK’s entire population. This observation tends to support the argument that political discourses on the Web are often limited to a handful (relatively speaking) of interested and invested users. It seems that mainly “hardcore” politics nerds and professionals in the field felt compelled to actively participate in online debates.

This leaves an ambiguous impression: on one hand, this appears as a considerable shortcoming in terms of pluralism (many political attitudes, especially different nuances, are not really represented); on the other, even if limited in their ideological scope, these on-site debates still tend to expand the informative content of each blog/website in a technical sense: potentially critical, different, or new perspective are added to the the original article. However, the ‘tone’ of debate reached partly extremely toxic levels and, depending on the context, could became downright aggressive.

Manifestations of verbal violence not unlike discursive forms that one normally associates with extreme forms of racism and dehumanisation frequently emerged in the sample. Especially politicians and other public figures became targets for offensive, hostile and vulgar comments:

It is indeed difficult to assess in how far these comments were genuine political positions or mere “trolling”. In any case, individual seemed to take advantage of their online anonymity to express their personal, sometimes very emotional positions in a rather uncivilised, practically violent manner that displayed features of hate speech.

Depending on the blog and audience, such provocative statements could find wider approval and initiate “rants” against the person or group in focus, who mostly happened to have a different political position. In this regard, party and A-List blogs in particular seemed to foster the rifts between political camps and hardened the fronts.

The Digital Transformation of Public Discourse

To sum up, in 2010 online media, especially political blogs, played an increasingly relevant role as information sources on different campaign programs; they also extended the spectrum of publicly communicated positions and attitudes, though different social filters determined the scope of actively partaking audiences. Party- and A list blogs tended to attract people who shared a certain set of political values, which diminished the potential for contestation and deliberation across ideological “silos”; at the same time, they occasionally served for intra-party discussions that could display the democratic-integrative features of consensus-seeking, deliberative discourse. However, forms of verbal violence, mostly addressed at the respective political opponent, were also part of political online debates and could reach extremely aggressive levels in some cases.

From a normative perspective, this leaves an altogether ambivalent impression and raises the question of whether this trend leads to a better informed, more transparent society – or whether it rather causes an increased fragmentation of our socio-economic lifeworld.

A significant different between the today and the last general election is the rise of the Eurosceptic-nationalist UKIP and the question about a referendum on Britain’s EU membership, which has gained in relevance over the past few years (the Eurozone crisis and systemic inconsistencies in the EU’s political framework may have contributed to this situation). The transnational developments on the European level are therefore potentially more relevant factors than in the previous election. In this respect, the entailed battles over national identity, sovereignty, transnational realities but also austerity measures may cause (or already have caused) extremely polarising, toxic online debates.

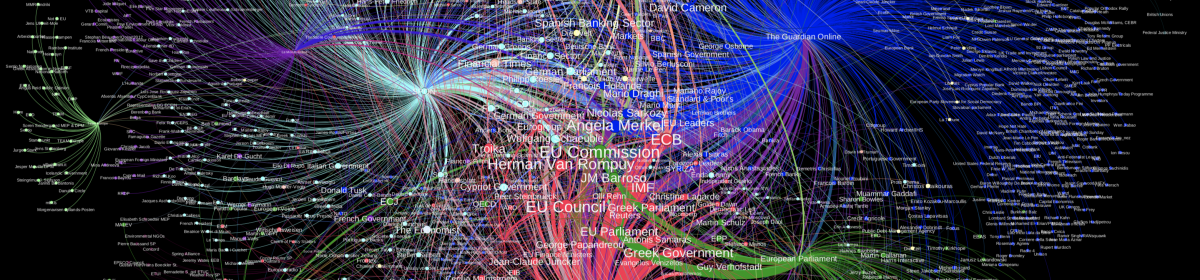

It is hardly disputable that the modes in which political stakeholders organised and executed their communication campaigns was accompanied by an increasingly relevant digital element, which only grew in importance in the past five years; more than ever, our current digitalised communication environment illustrates on a daily basis how media-based public discourse roots in a complex network of communication flows that are not confined to some separated “online” or “offline” space; both are intrinsically linked to each other and mutually affective.

Image courtesy of Unsplash.com

Addendum

Election campaigns tend to focus on ideals of justice/rightfulness, fairness, and morality. The current austerity debate and questions about immigration as well as nationalism are prime examples for this year’s general election. What is actually perceived as morality in politics is alway a question of framing.

George Lakoff’s work as a cognitive linguist is in this regard invaluable, since he shows the complex yet strong links between language, perception, values, morality and politics – all very important aspects that researchers in political communication need to consider: