UPDATE: This PhD proposal secured me a full scholarship – stipend and fees – at the University of Hull, where I completed my doctoral degree in March 2015. Though much of the methodology and empirical part changed over the course of the past three years, the basic research motivation(s) remained largely the same (but it was of course further refined to more precise research goals). Read the original below.

I’m pretty busy applying for PhD programmes these days and I have already sent some applications to universities throughout Europe. Though it still takes a few weeks before I get official responses, I have already received unofficial feedback – which has been quite positive. At the moment, my personal favorite is the City of London University (it offers great funding opportunities). Read my proposal, i.e. the research project I would like to work on in the next three years:

Proposal for a Ph.D. Research Project

Area of Studies: Media and Communications

Europe Online: Towards a Digital Transnational Sphere or Isolated Web Spaces?

A Comparative Study on the Structure, Function, and Scope of Contemporary Online Discourses in regards to Participation and Segmentation in the European Union

1. Introduction and Research Motivation

In 2011, the European Union faces substantial social, economic, cultural, and political challenges: The continuing economic crisis, increasing migration problems, environmental issues, and a shift towards the political right in various member states are only the most prominent ones. The EU is forced to communicate each political decision carefully to the continent’s population, particularly in such times of crisis; it actually needs to address a European public. Assessing the chances and limits of transnational public spheres within the geographical, political, and cultural spaces of the European Union is a recurring topic in academic discourses – most notably in communication and media studies (Bee/Bezoni et al. 2010; de Vreese 2010; Triandafyllidou et al. 2009). Various articles, case studies, and research projects on the issue exist. However, the majority of these approaches mainly focus the role of conventional mass media in ‘European’ public discourses (e.g. Balcytiene/Vinciuniene 2010; Berkel 2006; de Vreese 2002). Only a few academic contributions pay attention to online media and their relevance to processes of cultural, political, and social convergence in the EU (e.g. Jankowski/van Os 2004; Koopmanns/Zimmermann 2003). In fact, no larger empirical study has focused the Internet and its actual impact on European self-perception and public discourses beyond national frames yet (Risse 2003: 2).

As the distribution of the WWW continues to spread on the continent, examining online phenomena could yield important insights on tendencies towards ‘trans-nationality’ and a common ‘European’ identity. After all, citizens, the media, and political institutions have access to unprecedented technologies for communicative interaction that theoretically facilitate public debate and cultural exchange.

My research project will bridge this gap by analysing participatory online media and their potential for open transnational discourses, i.e. public spheres, in four stages:

I. The development of an elaborated theoretical framework for analysing and understanding transnational public spheres in the age of digital globalisation; this includes an in-depth revision and discussion of already existing notions of the public sphere (e.g. Habermas 1962, Noelle-Neumann 1998, Luhmann 1992, Sunstein 2007, Dahlberg 2007). By comparing and combining theoretical approaches from different academic cultures1, I will try to examine the subject-matter-of-consideration from a pluralistic perspective. Integrating theories on political communication, information societies (Webster 1995), digital democracy (Dean 2005; Lovink 2008), media convergences (Jenkins 2006; 2003), media audiences, and the formation of (transnational-)identities through discourse (Hall 2004) is crucial for achieving this. It is indispensable to include an analysis of the dominant discursive formations that determine the structure and outcome of online debates on and in the EU, i.e. the politics of in- and exclusion as regards participation in web-based discourses.

II. An extensive, comparative content analysis of EU-related online media and -debates in both quantitative and qualitative respect; this requires the development of a complementary methodological approach and the compilation of an appropriate text corpus.

III. Interviews with a selection of professional content providers in EU-related contexts (e.g. online journalists, EU-PR writers, popular bloggers), which I will conduct either off- or online (e.g. Skype); this allows me to evaluate the utilization of web technologies to ‘communicate’ Europe .

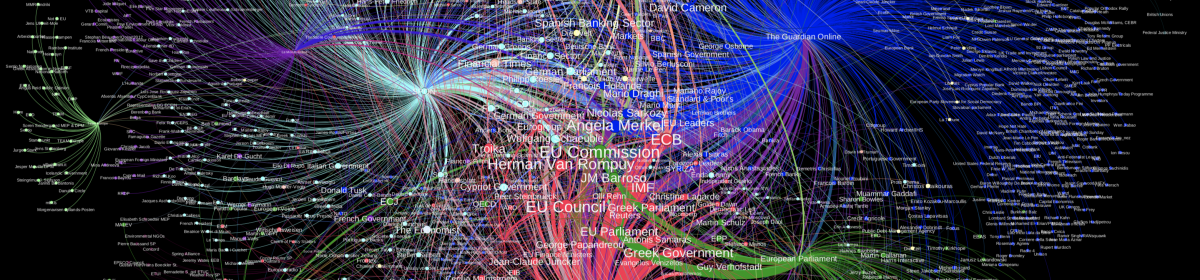

IV. Based on the findings of the previous steps, the establishment of a detailed taxonomy of EU-related online media, a characterisation of European ‘netizens’, and a map of transnational online networks of public spaces within the Union. Finally, I will be able to give substantiated answers to the question whether the Internet stimulates the emergence of transnational spheres or it rather promotes the demarcation of (nationally) isolated web-spaces – an important aspect in regards to the future course and success of the “European project” (Tisdall 2010). Ideally, the outcome of my research will also provide a methodological model that might be used to analyse similar phenomena in other web-based contexts.

2. Research Questions

In order to assess the structure, scope, and function of online content regarding the EU, I will approach and answer the following research questions, which are divided into three categories:

I. On the Potential of Transnational Public Spheres in European Information Societies: What online content on the European Union is available and does it add up to networked, digitalised public spheres across national borders, i.e. does the Internet actually facilitate the emergence of transnational, ‘European’ public debates? Where do they occur, what does their structure look like and what function do they have? What are the differences between the various online platforms (e.g. blogs, websites, Twitter, social media) as regards their potential for public debate in EU-contexts?

II. On the ‘Providers’ of Public Forums Online: What issues do professional content providers perceive to be ‘European’? What differences in identifying and evaluating ‘European’ issues do exist (e.g. national vs. transnational interests)? Where do the providers of content allocate themselves within Europe and its web- based environment? How does the EU communicate to the populations of its member states online?

III. On the Recipients/Users (and therefore possible ‘Europeans’): Who is participating in online discourses? Do the discussants reflect a certain ‘European’ self-conception? Who regards him-/herself to be European and where does this transnational self-perception collide with national identities? Do multilateral, deliberative-democratic discussions on controversial issues – such as climate change, migration, economy etc. – occur? Where do crucial short-comings in terms of openness and inclusion become apparent?

3. Data and Methodology

The core of this research project is an elaborate content analysis of online media platforms that focus the European Union and relevant trans- or international issues:

- Websites and forums provided by the institutions of the EU (e.g. European Commission 2010)

- Decidedly transnational, European news media online (e.g. European Voice 2010)

- A selection of ‘Europe sections’ from popular news media online, located in three important member states: the UK (e.g. Guardian.co.uk), Germany (e.g. faz.de), and France (e.g. lemonde.fr)

- A selection of blogs, Twitter-accounts, homepages etc. provided by decidedly ‘pan- European’ groups and organisations The text corpus will mainly consist of articles and posts, i.e. discourses, on websites, blogs, forums, and social networking sites.

To delimit the sample, I will set a temporal frame covering the years of ‘European crisis’ 2008 to 2010. The analysis aims for two levels: The “content-level”, i.e. the articles, blog-posts, Facebook-messages, Tweets etc. and the “comment level”, i.e. the direct responses from users/readers. The instruments for the data survey are a detailed codebook and data entry forms. Since it is not possible to gain satisfactory insights from a quantitative examination only, I will also analyse a sample of texts qualitatively by applying an adjusted form of critical discourse analysis (Richardson 2006). The second part of the data collection consists of interviews which will provide additional information for a deeper understanding of the intentions for utilising online media to address a public audience.

4. Conclusive Remarks

Ideally, my research project will develop an applicable theory to understand and analyse the structure, scope, and function of (transnational-)public spheres in contemporary, digitalised information societies and provide a complementary methodological approach to assess such phenomena both qualitatively and empirically. It could become a model to analyse similar phenomena in other web-based context.

By establishing a detailed taxonomy of EU- related online media and analysing the Web’s potential for transnational discourse, I will be able to highlight aspects in ‘communication on Europe’ that need further improvement on the side of professional content providers (e.g. EU-PR writers and online journalists focusing the EU). Moreover, it can bridge the gap between different academic cultures, i.e. connect and combine theoretical and methodological concepts from German Communication Sciences and Anglophone Communication- and Media Studies. Since I had the chance to study in both systems (and to receive both degrees), I am well aware of the different perspectives and approaches on one and the same field of study. Especially in regards to research on the public sphere, public opinion, and political communication, there is good potential for a productive exchange of findings and experiences.

5. List of References

Balcytiene, Aukse/Vinciuniene, Ausra (2010) ‘Assessing Conditions for the Homogenisation of the European Public Sphere: How Journalists Report, and Could Report, on Europe’, in: Bee, Christiano/ Bozzini, Emanuela (eds.): Mapping the European Public Sphere. Institutions, Media, and Civil Society. Farnham/Surrey: Ashgate: pp141-159.

Bee, Christiano/ Bozzini, Emanuela, eds. (2010): Mapping the European Public Sphere. Institutions, Media, and Civil Society. Farnham/Surrey: Ashgate: pp83-99.

Berkel, Barbara (2006) Conflict as a Catalyser for a European Public Sphere. A Content Analysis of Newspapers in Germany, France, Great Britain, and Austria. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Dahlberg, Lincoln (2007) ‘The Internet, Deliberative Democracy and Power: Radicalizing the Public Sphere’, International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics. Vol. 3 (1): pp.47- 64.

Dean, Jodi (2005) ‘Communicative Capitalism: Circulation and the Foreclosure of Politics’, Cultural Politics 1 (1).

De Vreese, Claes (2010) The EU as a Public Sphere. http://europeangovernance.livingreviews.org/Articles/lreg-2007-3/ (21/01/2011)

De Vreese, Claes (2002) Framing Europe: Television news and European integration. Amsterdam: Aksant Academic Publishers.

Erbe, Jessica, (2005) “’What Do the Papers Say? How Press Reviews Link National Media Arenas in Europe”, in Javnost – The Public, 12(2): pp75–92. European Commission (2010), http://blogs.ec.europa.eu/ (21/01/2011)

European Voice (2010), http://www.europeanvoice.com/ (21/01/2011)

FAZ (2010), http://www.faz.net/s/Rub99C3EECA60D84C08AD6B3E 60C4EA807F/Tpl~Ecommon~SThemenseite.html (21/01/2011)

Guardian (2010), http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/europe/roundup (21/01/2011)

Habermas, Jürgen (1996) The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. An Inquiry into a Category of Burgeois Society. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Hall, Stuart (2000) ‚Who needs identity’? in J. Evans / P. Redman eds. Identity: a Reader. London: Sage.

Jankowski, Nicholas/van Os, Renée (2004) “The 2004 European parliament election and the internet: contribution to a European public sphere?”, Conference on internet communication in intelligent societies, Hong Kong, conference paper.

Jenkins, Henry (2006) Convergence Culture. New York and London: New York University Press.

Jenkins, Henry / Thorburn, David (2003) ‘Introduction: The Digital Revolution, the Informed Citizen, and the Culture of Democracy’, in Jenkins, Henry / Thorburn, David, eds. Democracy and New Media. Cambridge/London: MIT Press.

Koopmans, Ruud/Zimmerman, Ann (2003) “Internet: A new potential for European political communication?”, WZB Discussion Paper, SP IV 2003-402, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, Berlin Le Monde (2010), http://www.lemonde.fr/europe/ (21/01/2011)

Lovink, Gert (2008): Zero Comments. Blogging and Critical Internet Culture. New York/London: Routledge.

Luhmann, Niklas (1992) “Observing the Observers in the Political System: On the Theory of Public Opinion”, in: Wilke, Jürgen (Hrsg.): Öffentliche Meinung, Theorie, Methoden, Befunde, Beiträge zu Ehren von Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann. Freiburg: pp77-86.

Noelle-Neumann, Elisabeth (1998) Public Opinion, in: Jarren,Otfried/Sarcinelli/Saxer(Hrsg.): Politische Kommunikation in der demokratischen Gesellschaft, Wiesbaden: pp81-93.

Risse, Thomas (2003) An Emerging European Public Sphere? Theoretical Clarifications and Empirical Indicators. Nashville: Paper presented to the Annual Meeting of the European Union Studies Association (EUSA).

Sunstein, Cass R. (2007) Republic.com. Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press.

Tisdall, Simon (2010) Has the Whole European Project Peaked? http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/may/11/european-union-euro-reform (21/01/2011)

Triandafyllido, Anna/ Wodak, Ruth/ Krzyżanowski, Michal, eds. (2009) The European Public Sphere and the Media. Europe in Crisis. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Webster, Frank (1995) Theories of the Information Society. London: Routledge.

IMPORTANT NOTE: It is not allowed to copy the contents – also in extracts – of this post/proposal. This text is, like any other content on this weblog, property of the author.