The seemingly never-ending Eurozone crisis made it into the news again this week with various media commentators arguing that the “Grexit” was (maybe) finally here. After all, the current Greek government seems yet again struggling to meet its “obligations” towards its European lenders, mainly represented by the ECB. A crisis meeting has already been announced, but it remains to be seen whether it will produce a real breakthrough. The month of April, so it seems, will decide over Greece’s future in- or outside the Eurozone. Déjà vu anyone?

The same had been said about January 2015, when the majority of Greeks resisted to the prevailing austerity drive by voting for radical left Syriza. In fact, similar claims about an end to Greece’s membership in the single currency union, if not even to the Euro’s continued existence as such, were made whenever the acting Greek government had to report to their international creditors over the past four years (see here, here, here, and here).

A potential “Grexit”, its probable impact, and an eventual collapse of the Eurozone have been repeatedly discussed by a variety of political commentators as well as economists – and for many it has long lost its “shock effect”. Not that anything has really changed in regards to the fundamental, potentially dramatic -and probably traumatic- consequences it would have for the single currency union and the political framework of the EU altogether.

However, it has become “the new normal” (Grusin 2010, citing brilliant comic artist Art Spiegelman) to live in an economic climate of constant crisis, fear for the future, depression, lack of innovation (not only in an economic but also political respect!) etc., just as Western societies have somehow accommodated themselves with a constant fear of religious terror since 9/11 (ibid). Against this background it is not really surprising that more optimistic assessments of the Eurozone’s future appear rather unconvincing to many.

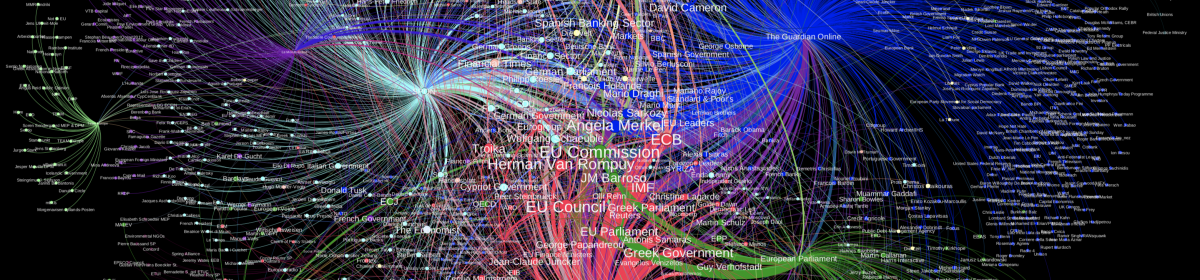

What’s interesting here from an analytical perspective on the EU crisis debate in the media is that almost any thinkable outcome of the crisis has been brought up in the transnational public sphere – and new analyses, evaluations, as well as prognoses are added on an almost daily basis. These seem to differ only slightly in their general narratives, which can be broadly separated into two categories: stories about the end of the Euro and stories about its eventual survival and/or success. However different both are in their general prognoses for Europe’s future, they seem to fulfil a similar function: they are attempts to reduce the level of surprise and to provide orientation for future actions.

Indeed, it seems that there hardly is a scenario that has not been thought through yet and the spectrum of expectable outcomes for the crisis were brought down to a handful of possibilities. Economists, political commentators, journalists and other public communicators are central drivers of this process since they, willingly or unwillingly, pre-fabricate “potential futures” through media communication (pre-mediated). These are repeated over and over again with small updates (re-mediated).

Premediation and the Eurozone Crisis – a Very brief Overview

Richard Grusin, Professor of English at Wayne State University, describes this process as ‘premediation’ (2010: 38), a logic ‘in which the future has always been pre-mediated‘ (ibid, original italics). According to him, in today’s highly mediatised society public communicators engaged in a style of discourse that moved away from the past and present to a mode of communication that placed increasing emphasis on “what could happen next (and what could come after that)”. Different scenarios and their outcomes are played through in public discourse by e.g. journalists, government representatives, experts etc. so that no eventual outcome comes truly unexpected.

Think of the different scenarios that exist for the outcome of austerity politics in the European context: while leading German politicians argue that fiscal discipline will lead to an economically stable, prosperous future, dissident voices claim that the same could actually increase the suffering caused by economic hardship across struggling Eurozone countries.

However, premeditation should not be confused with prediction, since premeditation served not for finding an ideal “result” to a specific development:

Unlike prediction, premeditation is not about getting the future right. In fact it is precisely the proliferation of competing and often contradictory future scenarios that enables premediation to prevent the experience of a traumatic future by generating and maintaining a low level of anxiety as a kind of affective prophylactic. Premediation is not like a weather forecast, which aims to predict correctly the weather for tomorrow, or the weekend or the week ahead. To premediate the weather would be to try imagine all of the possible scenarios that might conceivably arise so that the weather could never come as a surprise (ibid).

Grusin uses the US media landscape after 9/11 and during the War on Terror as his primary empirical example to describe the mechanisms of premeditation but his observations are transferable to other crises and conflicts, including the current Eurozone crisis. The political implications and the entailed clash of different future scenarios ingrained in framing processes, which dominate public communication, are of particular relevance for understanding the transnational public discourse in Europe:

To think of premeditation as characterizing the media regime of post-9/11 America is therefore to be concerned not with the truth or falsity of specific future scenarios but with widespread proliferation of premediated futures. Premediation entails the generation of possible future scenarios or possibilities which may come true or which may not, but which work in any event to guide action (or shape public sentiment) in the present. These scenarios are perpetuated both by governmental actors and by the formal and informal media […] (ibid: 47)

Premediation can serve as an instrument for framing a particular problem in a very specific way in order to achieve concrete political goals; claiming to know how the future will turn out often comes with precise agendas for how to organise current social, economic, and political orders. Seen from this perspective, the transnational public sphere currently takes the shape of a conflict-loaded communication sphere in which polarising scenarios compete with each other; this turns the crisis into a contest about the future as much as about the present.

There are plenty of examples, which include the debates on austerity/anti-austerity, integration and sovereignty, isolation and solidarity, Eurobonds, the financial transaction tax, bailout programmes, structural reforms etc. Once the future has been pre-mediated, it is instantly fed into the constant flow of remediation, i.e. the pattern of repetition in public discourse which creates an atmosphere of constant insecurity and anxiety that seems to characterise the “new normal” for many people in Europe.

References

Grusin, R. (2010): Premedation. Affect and Mediality after 9/11, London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.